What Genetic Mutation Increases Cancer Risk in Humans?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Discovery of a genetic mutation that increases cancer risk in humans.

- FasL protein is crucial for immune response but is compromised by plasmin.

- A single amino acid change in FasL enhances its vulnerability.

- Blocking plasmin may restore FasL's cancer-fighting abilities.

- Research may improve immunotherapy for solid tumors.

New Delhi, July 4 (NationPress) A group of researchers from the United States has discovered a genetic mutation that heightens the likelihood of cancer in humans, potentially leading to innovative therapies for this lethal ailment.

Scientists at the University of California Davis have elucidated why specific immune cells in humans struggle more than those in non-human primates to combat solid tumors effectively.

The findings, available in the journal Nature Communications, highlighted a minute genetic variation in an immune protein known as Fas Ligand (FasL) between humans and their non-human primate counterparts.

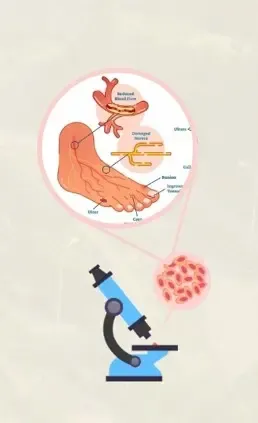

This genetic alteration renders the FasL protein susceptible to deactivation by plasmin, an enzyme associated with tumors. Such vulnerability appears to be exclusive to humans and is absent in non-human primates, such as chimpanzees.

“The evolutionary mutation in FasL may have played a role in the development of larger brain sizes in humans,” remarked Jogender Tushir-Singh, Associate Professor in the Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology.

“However, concerning cancer, this mutation represents an undesirable compromise, as it allows certain tumors to neutralize segments of our immune defense,” added Tushir-Singh.

FasL is a membrane protein on immune cells that initiates a process of programmed cell death termed apoptosis. Activated immune cells, such as CART cells derived from a patient's immune system, exploit apoptosis to eliminate cancer cells.

The UC Davis research team found that a singular evolutionary amino acid alteration -- serine instead of proline at position 153 -- makes FasL more vulnerable to cleavage and inactivation by plasmin.

Plasmin is a protease enzyme often elevated in aggressive solid tumors, including triple-negative breast cancer, colon cancer, and ovarian cancer.

This indicates that even when human immune cells are primed to attack tumor cells, one of their essential weapons -- FasL -- can be neutralized by the tumor environment, diminishing the efficacy of immunotherapies.

The results may clarify why CART and T-cell-based treatments are effective in blood cancers but often underperform in solid tumors. Blood cancers generally do not depend on plasmin for metastasis, while tumors like ovarian cancer heavily rely on plasmin for spreading.

Crucially, the study also indicated that inhibiting plasmin or protecting FasL from cleavage can restore its ability to kill cancer cells. This discovery could pave the way for advancements in cancer immunotherapy.

By integrating existing treatments with plasmin inhibitors or specially crafted antibodies that shield FasL, researchers may enhance immune responses in patients battling solid tumors.

“Humans exhibit a significantly greater cancer incidence than chimpanzees and other primates. There remains much to learn from primates that could enhance human cancer immunotherapies,” stated Tushir-Singh.

“This represents a substantial advancement in personalizing and improving immunotherapy for plasmin-positive cancers that have posed treatment challenges,” he concluded.