Is Judicial Intervention Necessary to Address Case Backlog? Insights from Ex-SC Judge Sanjay Kaul

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Case backlog is a significant challenge in the Indian judiciary.

- Former SC judge Sanjay Kishan Kaul advocates for filling judicial vacancies.

- Judicial infrastructure needs urgent improvement.

- Digitization can enhance efficiency but is insufficient without adequate judge capacity.

- Persistent judicial appointments are essential to managing case pendency.

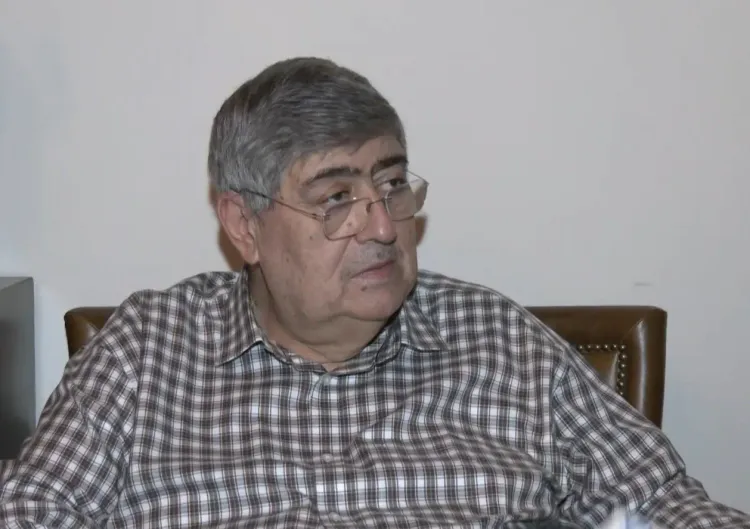

New Delhi, July 15 (NationPress) Identifying the issue of case backlog in the judiciary as a significant challenge, former Supreme Court judge Sanjay Kishan Kaul emphasized the urgent need for filling vacancies to tackle the pending cases. He mentioned that a judicial nudge may be required unless administrative actions are taken to resolve the vacancy crisis.

Justice Kaul stated, “Typically, at any given moment, there exists a one-third shortage of judges in High Courts, a trend that has been worsening over the years,” as he shared his views with IANS.

As of January, there were approximately 5 crore pending cases in the lower courts of India. The Supreme Court had over 80,000 pending cases, while High Courts faced a backlog exceeding 60 lakh.

While discussing the delays in appointments within the higher judiciary, Justice Kaul suggested that the government might still be reacting to the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling that invalidated the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC).

This Commission was proposed via a constitutional amendment to replace the existing Collegium system for appointing judges to the Supreme Court and High Courts.

“It seems that the government is taking its time to move past that situation,” remarked Justice Kaul, alluding to the perceived delays in the government’s process of approving judicial appointments recommended by High Courts.

He reiterated the necessity for a judicial push unless administrative measures are taken to resolve the vacancy concerns.

Justice Kaul also pointed out the importance of enhancing judicial infrastructure and urged timely allocation of funds to establish proper facilities, thus preventing any lapse.

“The infrastructure quality differs significantly across states. However, at one time, the Chief Justice of India initiated a monitoring process assessing judges' strength, infrastructure conditions, and court staff availability across all states,” he noted.

He acknowledged that while digitization enhances efficiency in the judicial system, meaningful improvements cannot be achieved if a judge is expected to handle 100 cases in a single day.

The Government asserts that it has been consistently working on filling judicial vacancies in both the Supreme Court and High Courts.

According to the Department of Justice, from May 1, 2014, to March 20, 2025, 67 judges were appointed to the Supreme Court, and 1,030 new judges along with 791 additional judges made permanent in the High Courts during the same timeframe.

The sanctioned strength of High Court judges has increased from 906 in May 2014 to 1,122 by February 2025.

Data from the Department of Justice indicates that as of February 28, 2025, the sanctioned strength in the district and subordinate judiciary was 25,786, while the actual working strength stood at 20,511.