Can Human Antibodies Neutralise Neurotoxins from 19 of the World’s Deadliest Snakes?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- The antivenom is derived from antibodies of a human with self-induced snake venom immunity.

- It has proven effective against multiple snake species in mouse trials.

- The research may pave the way for a universal antivenom.

- A small molecule inhibitor enhances the antivenom's effectiveness.

- Next steps include field testing in veterinary clinics.

New York, May 4 (NationPress) — Utilizing antibodies from a human donor who exhibited self-induced hyper-immunity to snake venom, researchers have successfully created the most broadly effective antivenom to date. This innovative antivenom has shown the ability to protect against the likes of the black mamba, king cobra, and tiger snakes in preliminary mouse trials.

Published in the journal Cell by Cell Press, the antivenom integrates protective antibodies with a small molecule inhibitor, paving the way for a universal antiserum.

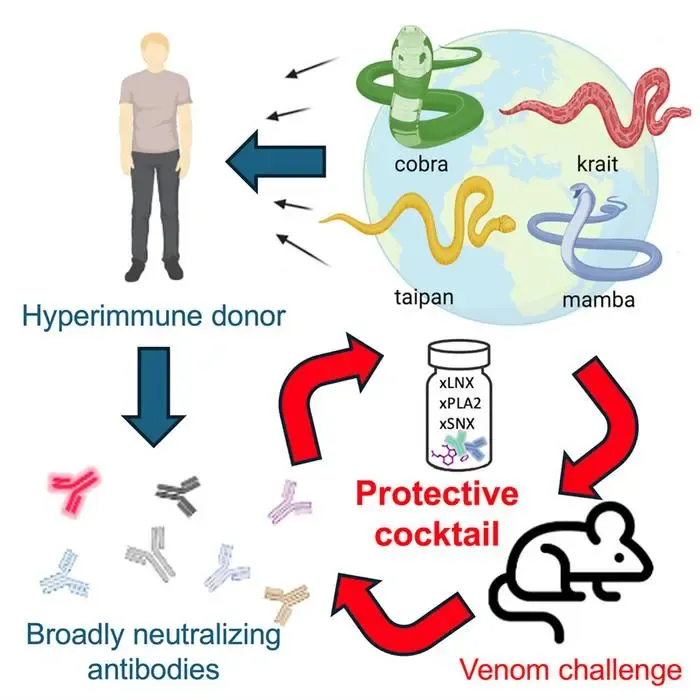

During their investigation, scientists encountered an individual who had developed hyper-immunity to snake neurotoxins. “The donor, Tim Friede, had endured hundreds of bites and self-immunizations with escalating doses from 16 species of exceptionally lethal snakes over nearly 18 years, which would typically be fatal to a horse,” stated Jacob Glanville, CEO of Centivax, Inc..

Upon agreeing to participate in the study, researchers discovered that Friede’s prolonged exposure to various snake venoms had led to the generation of antibodies that effectively neutralized multiple snake neurotoxins simultaneously.

“What made this donor remarkable was his extraordinary immune history,” Glanville noted. “Not only did he potentially produce these broadly neutralizing antibodies, but this could also lead to the development of a broad-spectrum or universal antivenom.”

To formulate the antivenom, the research team first created a testing panel comprising 19 of the World Health Organization’s most dangerous snakes, categorized within the elapid family, which includes approximately half of all venomous species, such as coral snakes, mambas, cobras, taipans, and kraits.

Subsequently, scientists isolated target antibodies from the donor’s blood that reacted with neurotoxins from the tested snake species.

Each antibody was systematically assessed in mice that had been envenomated by each species included in the panel. This approach allowed them to develop a cocktail that contained the minimum yet effective components necessary to neutralize all venoms.

To further enhance the antiserum, the team incorporated varespladib, a known toxin inhibitor, which provided additional protection against three more species.

Ultimately, they included a second antibody from the donor, known as SNX-B03, which broadened protection across the entire panel of snakes.

“By the time we reached three components, we achieved unparalleled protection for 13 of the 19 species, with partial protection for the remaining ones we examined,” Glanville stated.

With the antivenom cocktail showing effectiveness in mouse models, the team is now preparing for field tests, starting with administering the antivenom to dogs treated in veterinary clinics for snake bites in Australia.

Additionally, they aim to develop an antivenom targeting the other significant snake family, the vipers.