Can an Implantable Electronic Device Restore Movement After Spinal Cord Injury?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Implantable electronic devices can significantly enhance recovery for spinal cord injuries.

- The research indicates a potential for effective treatments in both humans and pets.

- Controlled electrical currents can stimulate healing and restore movement.

- The treatment has shown promising results without causing inflammation or damage.

- Future studies will refine the treatment protocols for optimal recovery outcomes.

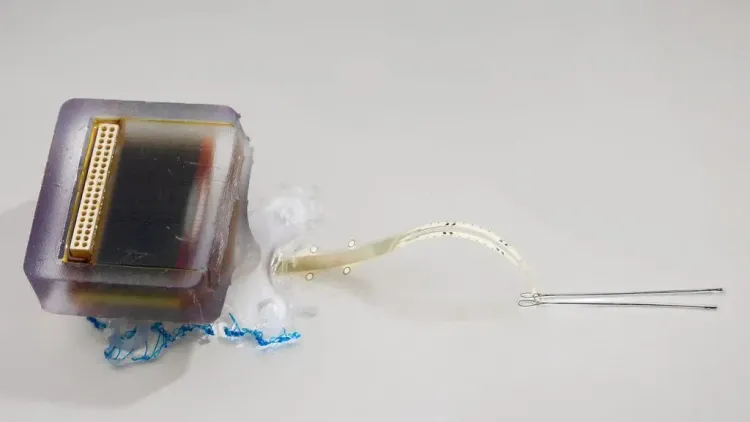

New Delhi, June 28 (NationPress) A group of researchers from Australia has successfully created an implantable electronic device that has restored movement after a spinal cord injury in an animal model, igniting hopes for a viable treatment option for both humans and pets.

Spinal cord injuries remain a significant medical challenge, often leading to devastating consequences for individuals. However, a recent trial conducted at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland, has unveiled promising prospects for effective therapies.

Lead researcher Dr. Bruce Harland, a senior research fellow in the School of Pharmacy at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland, stated, “Unlike a skin injury, which typically heals naturally, the spinal cord lacks the ability to regenerate effectively, making such injuries particularly severe and currently untreatable.”

Dr. Harland elaborated, “We have engineered an ultra-thin implant that is designed to rest directly on the spinal cord, precisely aligned over the injury site in rats,” as detailed in a paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

This device is capable of delivering a precisely controlled electrical current across the injury site.

Professor Darren Svirskis, director of the CatWalk Cure Programme at the University’s School of Pharmacy, emphasized, “The objective is to stimulate healing, enabling individuals to regain lost functions due to spinal cord injuries.”

In contrast to humans, rats exhibit a higher ability for spontaneous recovery following spinal cord injuries, allowing researchers to assess natural healing alongside healing facilitated by electrical stimulation.

After four weeks, the animals receiving daily electric stimulation displayed enhanced movement compared to those that did not.

Throughout the 12-week study, these animals demonstrated quicker responses to gentle touches.

“This suggests that the treatment aided in the recuperation of both movement and sensation,” Harland remarked. “Equally important, our analysis confirmed that the treatment did not induce inflammation or other harm to the spinal cord, proving it to be both effective and safe.”

The aim is to evolve this technology into a medical device that could significantly benefit individuals dealing with life-altering spinal cord injuries,” stated Professor Maria Asplund from Chalmers University of Technology. The next phase involves examining how varying doses, including strength, frequency, and duration of treatment, influence recovery to identify the optimal strategy for spinal cord repair.