Is it ironic that Pakistan, a terror sponsor, is now overseeing a counterterrorism framework?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Pakistan's counterterrorism claims are undermined by its support for militant groups.

- The irony of Pakistan leading a counterterrorism body is stark.

- Militant funding has evolved beyond traditional banking systems.

- The US-Pakistan relationship risks becoming too transactional.

- Pakistan must choose between cooperation abroad and complicity at home.

London, Oct 30 (NationPress) Pakistan's assertion of leadership in regional counter-terrorism is built on unstable foundations as its own land harbors, and often shields, the very organizations it claims to fight. A recent report indicates that Pakistan's involvement in regional counter-terrorism initiatives will remain a mere façade until its actions correspond with its rhetoric.

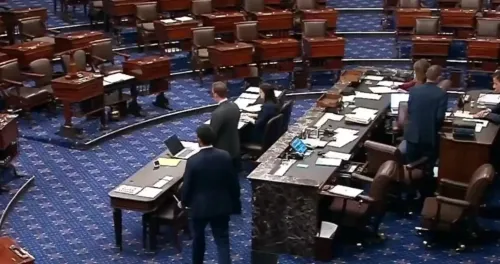

Last month, when Pakistan took the helm of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization's permanent anti-terror body, the Regional Anti-Terrorist Structure (RATS), the situation was striking: a nation known for sponsoring terrorism is now leading a regional group aimed at combating it. This irony cannot be overlooked. To enhance the credibility of Islamabad's international stance and domestic narrative, it is essential that its territory no longer acts as a sanctuary for groups that are trained and funded to target India. However, evidence indicates that this requirement remains unmet, as reported by the UK-based 'The Milli Chronicle.'

The report emphasized that Pakistan's persistent militant networks align closely with the country's long-standing military strategy of “bleeding India with a thousand cuts.” This involves using proxies and covert militants to impose costs on India while evading direct military confrontation.

According to US-based security analyst Siddhant Kishore, groups like Jaishe-e-Mohammad (JeM) and Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) serve tactical as well as ideological roles. If Pakistan genuinely intends to combat terrorism, then the lingering question is: why does Islamabad continue to support a system that blatantly contradicts its international responsibilities and its proclaimed commitment to counterterrorism?

The report cites the example of JeM, led by Masood Azhar, who continues to orchestrate operations, maintain training camps, and devise innovative fundraising methods. Despite suffering significant setbacks during Operation Sindoor, Azhar remains undeterred in his terrorist pursuits against India. In a recent address at a JeM facility in Bahawalpur, he announced the launch of a women’s jihad course, Jamat-ul-Mominat.

Pakistan’s counterterrorism narrative is further undermined by its financial oversight. Although Islamabad promotes its cooperation with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the funding for militants has advanced more quickly than its regulatory frameworks. Organizations like JeM have reportedly transitioned from conventional banking methods to fintech platforms, mobile wallets, and decentralized e-payment systems within Pakistan to sustain their activities. This digital evolution is not indicative of militant defeat but rather a testament to their resilience, as detailed in the Milli Chronicle report.

The report adds that Pakistan's deepening diplomatic and economic ties with the US could diminish Washington's influence over Islamabad's actions. Previously, US pressure occasionally compelled Pakistan's military intelligence to take action against militant proxies. However, the strategic dynamics appear to have shifted, as Pakistan now portrays itself as a “regional counterterror partner” and a reliable economic hub. The report indicates that Washington is prioritizing a transactional relationship over accountability, a development that could embolden Pakistan’s military leadership to exploit jihadist groups as tools of statecraft.

Pakistan’s claim to regional leadership in counterterrorism is on shaky ground as long as its territory continues to host — and often protect — the very networks it claims to oppose. The US–Pakistan relationship, increasingly transactional and disconnected from shared security objectives, risks reinforcing Islamabad’s belief that it can pursue dual strategies: cooperation abroad while remaining complicit at home. Until Pakistan aligns its words with its actions, its involvement in regional counterterrorism frameworks will remain superficial. The key question for the global community is not whether Pakistan can change, but whether it has the will to do so.