What Are the Security Challenges of Rohingya Repatriation in Bangladesh?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- The Rohingya crisis has escalated from a humanitarian issue to a national security challenge.

- Over 80,000 new refugees have entered Bangladesh since the previous government's fall.

- Engagement with the Arakan Army complicates repatriation efforts.

- Local Bangladeshis are facing security threats due to the ongoing conflict.

- International cooperation is vital for effective solutions.

Dhaka, Sep 9 (NationPress) The issue of repatriation for the Rohingya refugees, who fled Myanmar's military crackdown in 2017, was highlighted during Bangladesh's three-day international conference on Rohingya held in late August.

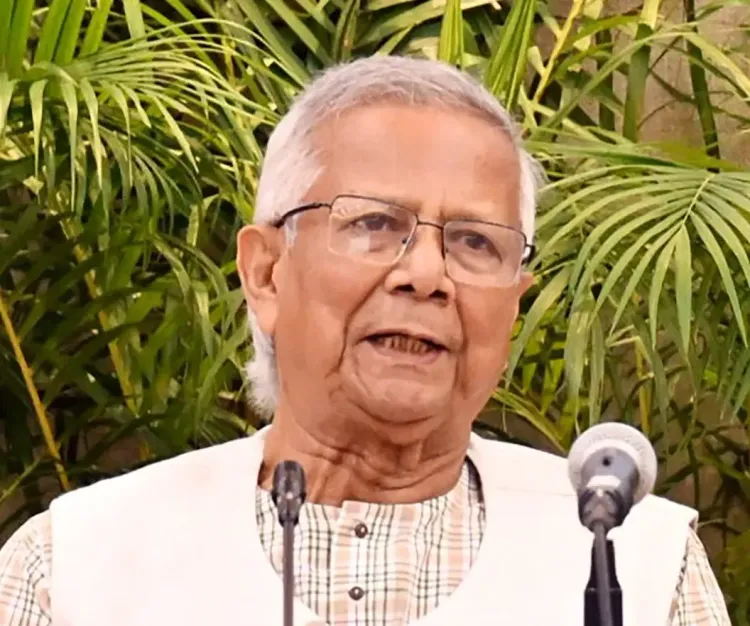

Since Muhammad Yunus took charge of the interim government in August 2024, the matter of Rohingya repatriation has gained policy significance, as he has positioned himself as a 'moral advocate'. Yet, this remains largely symbolic.

The influx of Rohingya refugees has surged since the previous government's collapse, with approximately 80,000 new arrivals added to the existing 1.2 million Rohingya already in Bangladesh.

The worsening situation of Myanmar's civil war, particularly with the Arakan Army holding significant territory in Rakhine bordering Bangladesh, has further complicated repatriation efforts. The Rohingya crisis has evolved from a refugee issue into a national security challenge for Bangladesh.

This year, Yunus has ramped up efforts for repatriation, including sending a letter to UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres regarding Myanmar's humanitarian crisis and inviting him to visit the Rohingya refugee camps in Cox's Bazar. They jointly vowed to work towards Rohingya repatriation by 'next Eid' and engaged in multilateral and bilateral discussions to gain cooperation on the repatriation issue, including the controversial proposal for a 'humanitarian corridor' from Cox's Bazar to Rakhine.

Despite Myanmar's junta verifying 180,000 Rohingyas for return, actual repatriation remains a distant hope, as no returns have occurred.

Additionally, Bangladesh has engaged in communication with the Arakan Army, which controls 14 out of 17 townships in Rakhine state, despite objections from Myanmar's junta. Dhaka defends this engagement as a move to protect its national interests.

While the Arakan Army seeks legitimacy in Rakhine through its interactions with Dhaka, Bangladesh's strategy remains ambiguous, especially following the Arakan Army's military advances that led to a new Rohingya exodus from Buthidaung and Maungdaw in December 2024.

Furthermore, the rebel group has not formally consented to take back the Rohingya refugees, which is the primary reason for Bangladesh's communications with them. In contrast, a June report from Human Rights Watch highlighted that the Arakan Army has been oppressing Rohingyas in northern Rakhine.

The overcrowded Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, suffering from inhumane conditions exacerbated by a shortfall in international aid, have become vulnerable to the Rohingya armed groups, especially the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA). These groups have militarized the camps, engaged in drug and arms smuggling, and drawn border conflicts into Bangladeshi territory.

Through aggressive recruitment of Rohingya youth from these camps, armed groups are now fighting against the Arakan Army. Such activities have not only obstructed repatriation efforts but also destabilized the situation in southeastern Bangladesh.

The conflict in Myanmar has also impacted Bangladeshi civilians. Recent violent escalations along the Teknaf border, including shelling and gunfire from Rakhine, have threatened the safety of local Bangladeshis, instilling fear and disrupting their livelihoods.

This has prompted further Rohingya influx attempts. Additionally, the repeated abduction of Bangladeshi fishermen from the Naf River and adjacent maritime areas by the Arakan Army has posed significant challenges to Bangladesh's cross-border security.

The Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) reported at least 230 abduction cases in the past eight months, including 46 in the last three weeks. Experts suggest that the Arakan Army's isolation and resource scarcity may drive these abductions.

Consequently, it's plausible that the rebel group could pressure Bangladesh to open a humanitarian corridor for aid supplies, a proposal initially entertained by the interim government but later retracted due to political backlash.

Given the ongoing conflict in Myanmar, it is clear that such a corridor could be exploited to sustain conflict rather than facilitate humanitarian efforts, sidelining the crucial issue of Rohingya repatriation.

Once an economic burden for Bangladesh, the Rohingya issue has morphed into a political and security dilemma. The recent international conference on Rohingya, titled 'Stakeholder Dialogue: Key Messages for the High-Level Conference on the Rohingya Situation', represents Yunus's latest attempt to rekindle international engagement on this urgent matter.

However, miscalculations in policy seem to be causing more harm than good. Despite Yunus’s diplomatic efforts to foster international cooperation, responses have largely been superficial. With the chief advisor acknowledging they have 'reached all its limits', it is evident that a genuine commitment to Rohingya repatriation is required. Bangladesh must reassess its policies, keeping both border and regional security in focus.

As we approach the scheduled UN meeting in New York later this month, it remains to be seen whether it will yield mere international solidarity or tangible cooperation towards Rohingya repatriation.