Is This a Recalibration Moment for US Power? Rubio's Perspective

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Rubio emphasized the need for prioritization in foreign policy.

- The press conference format was unconventional, starting from the back row.

- He discussed the importance of bilingual communication in addressing Latin American issues.

- Rubio stressed that US power is finite and requires disciplined application.

- Diplomacy is a slow process that requires careful navigation of global challenges.

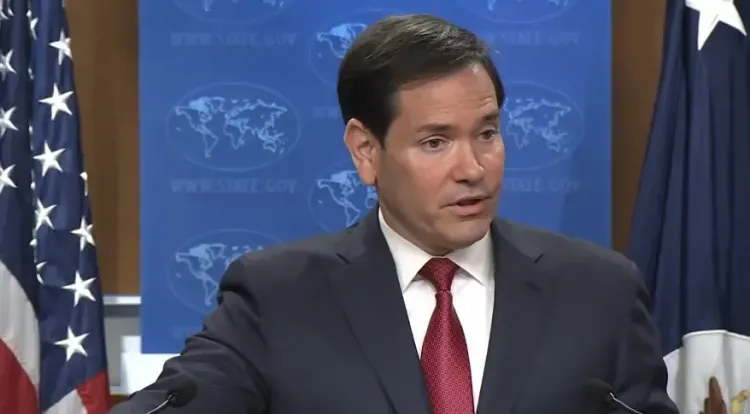

Washington, Dec 20, (NationPress) The press conference commenced unusually, diverging from the typical format seen in Washington. Instead of directing his attention to the usual front row, Secretary of State Marco Rubio leaned back, surveyed the room, and declared a change in protocol. "I'm going to start from the back row forward," he stated before proceeding to do just that.

Over the ensuing two-plus hours, Rubio methodically made his way to the podium, ensuring every raised hand was acknowledged, pausing for follow-ups, and returning to anyone he felt had been overlooked. "I'll be here pretty long, so don't get desperate, don't get wild," he reassured reporters early on -- a commitment he largely fulfilled.

This seemingly minor procedural adjustment set a tone for the subsequent discussion: a relaxed, comprehensive year-end dialogue focused less on sound bites and more on navigating a complex global agenda while recognizing the limitations of American power.

From the very start, Rubio framed the moment as one of evaluation rather than proclamation. "At the core of foreign policy needs to be the national interest of the United States," he reiterated, emphasizing that foreign policy is fundamentally an exercise in prioritization.

"Resources have limited time, and it has to be able to dedicate those resources and time through a process of prioritization," Rubio stated, noting that the global landscape for which US foreign policy institutions were initially established "no longer existed".

He contended that this recalibration does not equate to withdrawal. "That doesn't mean we don't care about what happens in the world," he asserted. However, in Rubio's view, caring must align with discipline and a realistic understanding of what US power can effectively achieve.

As questions progressed by region, another notable shift in Washington protocol became apparent. Rubio fluidly transitioned between English and Spanish, fielding nearly a quarter of the inquiries in Spanish and responding first in that language before reiterating them in English for the audience.

"I can do English. I'll answer Spanish if you ask Spanish, and then I'll answer it in English," he remarked early on.

This bilingual approach was more than just linguistic; inquiries regarding Venezuela, Colombia, narcotics trafficking, and regional security flowed seamlessly in Spanish, with Rubio treating them as central issues of US foreign policy.

The Western Hemisphere, often overshadowed by crises in other areas, took on significant prominence in his remarks.

"There's one place that doesn't cooperate, and it's the illegitimate regime in Venezuela," Rubio accused, claiming Caracas is openly collaborating with "terrorists and criminal elements" as well as drug trafficking organizations.

On a more positive note regarding other nations in the region, he stated, "So the good news is we have a lot of countries in the region that openly cooperate and work with us," highlighting Mexico as a nation where cooperation with the US is at an all-time high.

If Latin America revealed sharp contrasts, the Middle East showcased cautious sequencing. Regarding Gaza, Rubio acknowledged the ongoing conflict but maintained that its nature has shifted. "There is now a ceasefire," he remarked, adding that "there's more work to remain."

He suggested that the next steps should focus on governance rather than military presence. "The next step here is announcing the Board of Peace, announcing the Palestinian technocratic group that will help provide daily governance," he said.

Only after these steps, he argued, can discussions about stabilization forces be addressed. In this context, Pakistan emerged as a potential contributor. "We're very grateful to Pakistan for their offer to be a part of it or at least their offer to consider being a part of it," Rubio expressed, while emphasizing that nations require clarity on "what the mandate is" and "what the funding mechanism looks like."

In the context of Ukraine, the tone shifted from cautious optimism to stark realism. "We don't see surrender anytime in the near future by either side," Rubio noted, framing negotiations as a necessity rather than a choice.

"There's only one nation on earth… that can actually talk to both sides," he stated. "And that's the United States." However, he was equally clear about limitations: "This is not about imposing a deal on anybody," he clarified. "The decision will be up to Ukraine and up to Russia."

In the Indo-Pacific, Rubio dismissed the notion of clear-cut dichotomies. "Look, there will be tensions, there's no doubt about it," he remarked regarding China, labeling it "a rich and powerful country and a factor in geopolitics."

"We have to have relations with them. We have to deal with them," he asserted, while reaffirming alliances with Japan and partnerships across the Indo-Pacific, including India.

He indicated that the objective is not to eliminate tensions but to manage them — to "balance these two things."

Conversely, he described the situation in Sudan in stark moral terms devoid of diplomatic embellishments. "What's happening there is horrifying," he lamented, expressing concern over broken commitments and external meddling. The primary focus, he indicated, is singular: "Our number one priority… 99 per cent of our focus is this humanitarian truce."

Even in Lebanon and Israel, Rubio refrained from making predictions. "No one is in favour of a Hezbollah that can once again threaten Israel's security," he emphasized, underscoring that lasting stability hinges on "a strong Lebanese government that can actually control the country."

By the time Rubio concluded his statements — more than two hours after the conference began — the atmosphere felt more like a collaborative workshop than a performance. The back-to-front format, the bilingual interactions, and the absence of time constraints reinforced a recurring message: diplomacy is a gradual, imperfect process, constrained by realities that slogans cannot dissolve.

"Foreign aid is not charity," Rubio remarked at one point. "It's an act of the US taxpayer."

In Rubio's view, power is limited, peace is conditional, and foreign policy, stripped of rhetoric, involves the diligent task of deciding where to engage, where to exert pressure, and where to accept limitations.

In a world filled with overlapping conflicts and competing priorities, Rubio's extensive year-end reflection provided not a sweeping doctrine but a framework — one grounded in national interest, shaped by constraints, and executed, question by question, from the back of the room forward.