Can Pre-Trial Detention Be Considered Punishment? Insights from Ex-CJI D.Y. Chandrachud

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Pre-trial detention should not be treated as punishment.

- The presumption of innocence is a foundational principle in Indian law.

- Generational empathy is vital for understanding modern legal challenges.

- Judicial accountability is crucial in combating corruption.

- Prolonged trials violate the right to a speedy trial under Article 21.

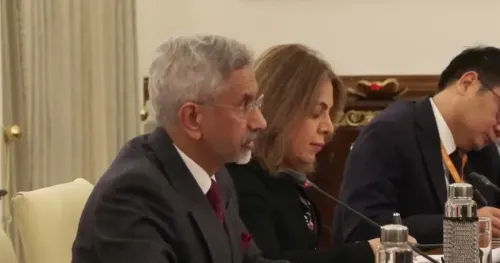

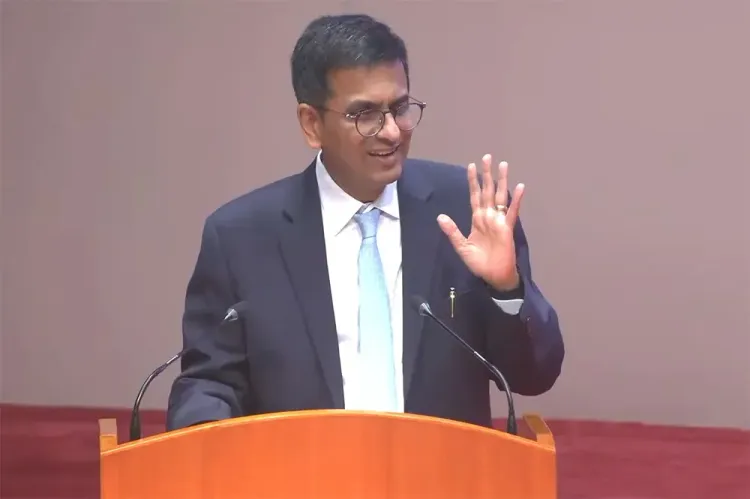

Jaipur, Jan 18 (NationPress) Former Chief Justice of India, Justice D.Y. Chandrachud, shared his candid and extensive thoughts on law, democracy, the bail process, and judicial operations during a session at the Jaipur Literature Festival. He provided unique personal and institutional perspectives informed by his tenure on the Bench.

Chandrachud emphasized the importance of understanding different generational perspectives, noting that while he belongs to the Baby Boomer cohort, his daughters, who are part of Generation Z, have special needs. He stated, “To stay connected with them, I must grasp how Gen Z thinks and operates,” highlighting the significance of empathy and adaptability across generations.

In relation to his recent publication, he clarified that it is not a traditional legal book but rather a collection of his speeches. This format naturally incorporates diverse influences, including rulings from the Indian and American Supreme Courts and philosophies from prominent thinkers like John Stuart Mill and Immanuel Kant.

Reflecting on the pivotal ruling that decriminalized homosexuality, he cited inspiration from a line by Leonard Cohen, illustrating the delicate balance of democracy and the enduring hope that accompanies it. He remarked, “Some judgments are straightforward, while others demand a touch of thoughtfulness and sensitivity.”

Addressing questions regarding the Umar Khalid case, he made it clear that he was expressing his views as a citizen, not as a judge. He reaffirmed that the bedrock of Indian criminal law is the presumption of innocence and emphasized that pre-trial detention should not be equated with punishment.

Chandrachud raised concerns about how the state could compensate individuals who spend five to seven years in jail as undertrials only to be acquitted later. He articulated that bail should only be denied under limited circumstances—if the accused represents a serious threat to society, is likely to flee, or may tamper with evidence. In the absence of these factors, “bail should be the default,” he maintained.

He also expressed worries about national security laws, stressing the need for courts to evaluate if detention is both necessary and proportionate. He cautioned that lengthy trials infringe upon the right to a speedy trial as guaranteed by Article 21.

Former CJI Chandrachud voiced apprehension about an increasing culture of fear within district and High Courts, where judges are reluctant to grant bail due to fears of scrutiny and potential career impacts. This, he noted, places an overwhelming burden on higher courts, with the Supreme Court managing nearly 70,000 cases each year.

On the topic of corruption, he underscored the necessity for robust accountability systems, warning against the inclination to label every unfavorable decision as corrupt. He concluded that fortifying institutions is the genuine pathway to justice.