How Are Pakistani Smugglers Taking Advantage of British Oversight in Transboundary Drug Trafficking?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Transboundary drug trafficking is a systemic threat fueled by gaps in enforcement.

- Pakistan's role in drug smuggling is often due to local facilitators acting unchecked.

- Stronger cooperation between countries is crucial to combat these networks.

- Intelligence-led operations must be prioritized to address the issue decisively.

- Enhancing customs monitoring can prevent drug shipments from reaching their destinations.

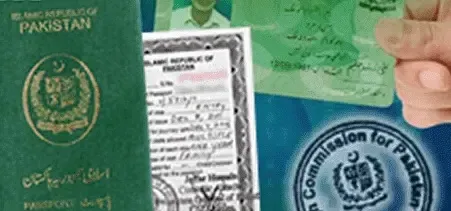

Islamabad, Dec 29 (NationPress) The situation surrounding Sidrah Nosheen, a 34-year-old woman sentenced to 21 years in a UK prison for her role in a gang involved in smuggling heroin from Pakistan, highlights the alarming evolution of transboundary drug trafficking into a systemic danger. This illicit trade thrives on weaknesses in immigration enforcement, enabling networks to operate with a degree of impunity.

Nosheen was a key member of an Organised Crime Group (OCG) that transported heroin from Pakistan to the UK and distributed it nationwide. Her involvement in this OCG was significant.

According to reports from The Express Tribune, transboundary drug trafficking has turned into a major threat, thriving on enforcement gaps and lax immigration controls, which allow networks to function with minimal oversight. This international operation takes advantage of vulnerabilities at both ends of the supply chain, while societies suffer the human and reputational toll. Pakistan is frequently implicated, not due to the inherent culpability of its citizens, but because local facilitators act unchecked, allowing global networks to prosper.

The case of Nosheen, presented in Bradford Crown Court, uncovers the extensive and intricate nature of these drug trafficking networks.

Her operation, involving £8.5 million worth of heroin, relied on connections in Pakistan to manage shipments while maneuvering around British oversight. The drugs were cleverly hidden within clothing, household items, and tools, a stark reminder that the drug trade adapts to everyday life, exploiting procedural loopholes to evade detection. As a result, she received a 21-year prison sentence. The challenges are not confined to foreign lands; Pakistan's law enforcement, despite being active in drug seizures and arrests, remains largely reactive.

Initially scheduled to face trial at Bradford Crown Court, Nosheen changed her plea to guilty for conspiracy to supply and import heroin. She was sentenced on December 23. The National Crime Agency (NCA) reported that heroin, concealed in leather jackets, was sent to Nosheen's residence in Woodside Road, Wyke, Bradford, where she repackaged it into 1kg bags.

Upon her arrest in June 2024, authorities discovered that her back bedroom had been transformed into a heroin processing facility, uncovering 85kg of Class A drugs packed in various bags, alongside equipment like a wallpaper pasting table, scales, and buckets.

The Express Tribune emphasized that leads from international investigations are often stymied by bureaucratic delays in Pakistan. Drug cartels exploit these delays, acting more swiftly than authorities can respond. It is crucial for Pakistan to enhance intelligence-driven operations and take decisive action on leads originating from other countries.

“Middlemen and facilitators must be dismantled before shipments leave the country. Coordination with destination nations should be proactive rather than reactive. At the same time, countries like the UK should strengthen customs and postal monitoring to intercept shipments at multiple stages, rather than depending solely on post-factum arrests. Pakistan must tackle this issue not just for enforcement's sake but to safeguard its populace and international reputation,” the report concluded.