What Was the First Principle of British Foreign Policy: Protecting England by the Finances of India?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- The EIC's debt burden significantly impacted India's economy.

- Wellesley's policies led to rampant financial mismanagement.

- The British Parliament prioritized financial interests over Indian welfare.

- Colonial governance was driven by economic motivations.

- Understanding this history is essential for recognizing ongoing impacts.

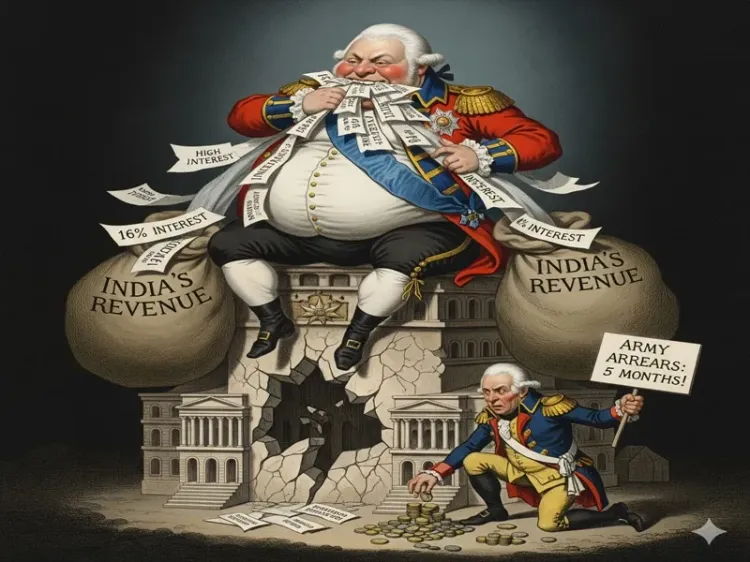

New Delhi, Nov 30 (NationPress) In the early 1800s, countless inhabitants of the rich lands of Hindustan faced their most formidable foe—not a rival sovereign or an invading force, but a pervasive, suffocating debt. This debt, engineered by the insatiable ambitions of the British East India Company (EIC) under Governor-General Marquis Wellesley, became the most devastating burden placed upon the subcontinent.

Wellesley’s renowned subjugation of the Mahratta Confederacy and annexation of affluent territories such as Oude were financed not by the EIC’s treasures but through exorbitant, high-interest loans acquired within India. The end result was a staggering inflation of Indian debt from approximately £11 million to more than 31 million pounds.

When this financial disaster returned to London, the response was immediate, frantic, and highly revealing. The parliamentary discussions of 1805 and 1806 exposed the foundational tenet of Britain’s foreign policy concerning the subcontinent: the focus was not on the welfare of India, but on the urgent need to safeguard the British Exchequer from the financial fallout of its own imperial ambitions.

The intense struggle was articulated most vehemently by individuals like Mr. Francis, who stated his only remaining objective was to "shield England not from the company, but from India and its governance". This chilling declaration underscored the deepest anxieties of the Indian populace: the conquered lands were no longer viewed as sources of pride or profit, but as a disease threatening to engulf the "mother country" itself.

I. The Emperor's Reckoning: Wellesley’s Excess and the Debt Machine

The overwhelming debt that endangered the EIC's survival was a direct consequence of a governance system steeped in "despotic power" and "wasteful extravagance". Marquis Wellesley’s famed regime ignored the Company’s pledged duty to exercise prudence and fiscal responsibility, opting instead for a lavish display of royal opulence.

Wellesley’s expenditures were characterized as "wasteful, extravagant, and unauthorized use of public funds". He financed projects such as the Calcutta Palace, constructed at a staggering cost of 220,000 pounds, a level of luxury "unmatched even among Eastern monarchs". Furthermore, despite legal prohibitions against accepting funds from locals, he was accused of receiving upwards of 120,000 pounds for his "personal indulgences".

This personal extravagance, combined with unending warfare, ensured that the significant revenues from annexed provinces were immediately consumed by interest payments. The colossal debt was incurred at high rates, nominally around 10 or 12 percent, but due to unfavorable financial practices, real interest rates on loans soared to 16 percent. This established a debt machine that devoured British credit, indicating that the "increase in investment... must be interpreted as representing, not surplus revenue, but the growing debt of India".

As Mr. Francis starkly remarked: "commerce generated factories, factories necessitated garrisons, garrisons created armies, armies led to conquests, and conquests have led us to our current predicament".

II. The Dismal Condition: Cornwallis Acknowledges Ruin

The true extent of this financial calamity became evident in 1805 with the reappointment of Lord Cornwallis, who arrived in India intending to rectify Wellesley’s expansionist policies, only to discover the finances in a "dismal state".

Cornwallis’s evaluation, which soon reached Parliament, painted a picture of an empire on the brink of collapse, incapable of meeting its basic operational expenses:

Army Arrears: The regular soldiers were "nearly five months" overdue on pay, with public departments "even further in arrears".

The Pricey Irregulars: The most pressing issue was the enormous contingent of irregular troops costing around £60,000 sterling monthly. Cornwallis had no choice but to disband them, deeming this expenditure "far more damaging to the company than their opposition in battle could ever be".

Seizure of China Treasure: In order to address these crushing arrears, Cornwallis resorted to extreme, illegal measures. He felt the "absolute necessity of seizing the company’s treasure intended for the China trade", totaling £250,000. He also urged the Madras government to release £50,000 of the funds allocated for their presidency.

This seizure of treasure represented a commercial crisis: funds essential to the EIC's crucial trade with China—the very enterprise that founded the Company—were illegally commandeered to prevent military insurrection. The internal turmoil within the Indian administration was so severe that the Governor-General had to betray the Company's commercial interests to keep the military operational. This confirmed that the "costs of warfare had already caused significant harm to this nation".

III. The Legal Fiction: The Annual Half-Million

The EIC's failures were further magnified by its legal commitments to the British public. The renewal of the Company’s charter in 1793 came with a stringent financial obligation: the EIC was required to pay the government 500,000 pounds annually from the surplus profits of its trade, with the Company’s assets in England responsible for payment. This sum was the symbolic cost of their sustained monopoly and a demonstration that India was contributing to the national treasury.

While the law allowed for deferral in wartime, the truth uncovered during parliamentary inquiries was damning: the Company had "never paid any portion" of this mandated amount.

Although the EIC could argue that the prolonged European conflict hindered surplus profits necessary for payment, the dramatic increase in Indian debt indicated that India was not merely failing to generate profit for Britain; it was swiftly evolving into a financial burden threatening to drag the mother country down. The EIC, legally bound to contribute to the national treasury, was instead covertly accumulating debts that would ultimately require British taxpayers to support the colonial framework.

IV. The New Foreign Policy: Protecting England from Its Own Empire

The financial exposure of the EIC necessitated a shift in policy rhetoric, most forcefully expressed by Mr. Francis, a seasoned critic of the conquest system. Francis, who had previously strived to "maintain the peace of India, and to protect native rulers... from injustice, conquest, and oppression", now viewed his ultimate, most critical task as purely defensive for the homeland.

His assertion—"The only duty left for me... is to shield England not from the company, but from India and its governance"—was not an act of abandoning the Indian populace, but a practical acknowledgment that the only way to halt the "wasteful extravagance" and "destructive conquests" was to persuade Parliament that the chaos would inevitably cross the ocean.

Francis contended that the problems originating in India "would not remain confined to that region". He cautioned that India, under its current management, provided "no revenue", instead draining British resources and the "finest of our troops" in "devastating conquests". He believed that the EIC's insolvency was imminent and that it was merely a matter of time before members of the House would have to "protect the finances of this nation against the tribulations of India".

By framing the issue as a danger to British financial stability, Francis sought to instigate a fundamental transformation in governance principles, advocating for a system of "jealousy, justice, and moderation" to be established in India. He urged the British to adopt a defensive foreign policy in Asia—not against the Mahrattas or the French, but against the financial self-destruction of their own colonial state.

V. The Quest for a Shield: Lord Castlereagh's Guaranteed Loan

The government, acutely aware of the vast debt and the threat it posed to the EIC's capability to sustain its trade and meet future obligations, sought a solution that would stabilize India without burdening the national budget with immediate transfers. The approach focused on converting the costly Indian debt into more manageable European debt.

Lord Castlereagh, although initially dismissing any "pessimistic view" of the Company's situation, acknowledged that "something needed to be done urgently to assist the Company". He proposed raising a large loan "with parliamentary approval".

The objective was pragmatic: to transfer a significant portion of the Indian debt (estimated by some to be as much as 17 million pounds, and by Castlereagh at about £16 million) from the high-interest Indian market to the lower-interest English market. Castlereagh argued that this loan would be raised "more favorably" under parliamentary guarantee than if the Company, whose solvency was constantly in question, sought it on its own.

The proposal mirrored the loans raised for Ireland prior to the union: the public would guarantee the loan, and the EIC's Indian revenues would be mortgaged for repayment.

Key aspects of Castlereagh’s plan underscored the emphasis on protecting the Exchequer:

1. Financial Benefit: Transitioning debt incurred at 10-12 percent (or even 16 percent) to European rates would yield an immediate saving of around 800,000 pounds per year.

2. Securing Public Payment: This annual saving would, in turn, be utilized to secure the government's rightful 500,000 pounds annual contribution, an obligation the EIC had consistently failed to fulfill.

3. Security and Precedence: The loan was to be secured against the territorial revenues guaranteed by Parliament, set aside immediately after military expenses. Castlereagh insisted that the risk was no greater than the precedent established by the Irish loans, arguing that "short of the case of our absolute expulsion from India, it was impossible to question the nature of the security".

Castlereagh framed the measure as one that would "add 800,000 pounds a year to the Company's revenue" and thus secure the public's own 500,000 pounds share. Therefore, the solution was not a humanitarian aid package for India, but a complex financial maneuver: leveraging the immense credit of the British nation to stabilize a colonial economy that was collapsing due to imperial overreach, ultimately ensuring that the "mother country" received its long-overdue profits.

Conclusion: The Ultimate Subjugation

The examination of India's finances in the British Parliament during this period reveals a stark, unvarnished perspective on colonialism. The conquest system, driven by Wellesley's "schemes of conquest and expansion of dominion", resulted in vast territorial gains but left India with staggering debt and a financial framework on the brink of collapse.

When Lord Castlereagh offered a government-backed loan, it was not an act of benevolence but rather a strategic measure for self-preservation. It was the ultimate, necessary step to prevent the financial contamination of the British state by its own failing colonial endeavor. Francis’s concern that the British would have to "shield the finances of this country against the tribulations of India" had come to fruition.

For the people of India, the final affront was that this solution did not erase the debt—it merely transformed it. The loans, now backed by the Crown's credit, ensured that the burden would be everlasting, with its payment guaranteed by mortgaging the complete revenue of the conquered land. The high-interest loans held by Indian financiers were exchanged for cheaper European bills, solidifying the economic transfer of wealth from Hindustan to the metropolis.

The EIC’s aggressive territorial expansion thus culminated in the establishment of an impenetrable financial chain. The First Principle of Foreign Policy was successfully implemented: India was neutralized as a threat to Britain’s prosperity, not through military force, but by shifting its vast, unsustainable debts onto the sovereign credit of the Crown, thereby securing the empire's financial integrity at the expense of India's long-term economic prospects. It was a clear affirmation that while the conqueror's glory may fade, the banker's lien persists indefinitely.