What Inflammatory Pathways Contribute to Asthma Attacks in Children?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Inflammatory pathways play a crucial role in asthma flare-ups.

- Eosinophilic asthma is driven by type 2 inflammation.

- New research identifies additional inflammatory drivers of asthma exacerbations.

- Personalized treatment strategies are essential for effective asthma management.

- Understanding these complexities can enhance the quality of life for affected children.

New Delhi, Aug 2 (NationPress) Researchers have uncovered inflammatory pathways that lead to asthma flare-ups in children, even in cases where treatment is administered.

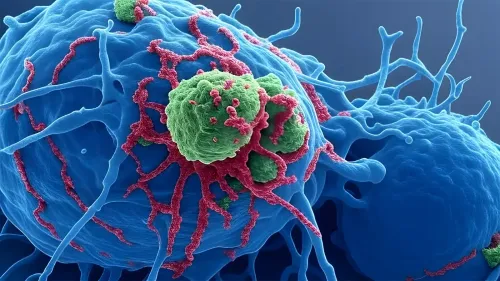

Eosinophilic asthma is marked by elevated eosinophils, a type of white blood cell that plays a role in the immune response. Although eosinophils typically assist in combating infections, in eosinophilic asthma, they build up in the lungs and airways, resulting in chronic inflammation, swelling, and harm to the respiratory system.

This form of asthma is largely influenced by type 2 (T2) inflammation, an immune response involving cytokines that encourage the production and activation of eosinophils.

Consequently, therapies aimed at reducing T2 inflammation are employed to lower eosinophil levels and avert asthma flare-ups.

“However, even with targeted therapies against T2 inflammation, some children continue to have asthma attacks. This indicates that additional inflammatory pathways may also contribute to exacerbations,” stated Rajesh Kumar, Interim Division Head of Allergy and Immunology at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago, US.

In research published in JAMA Pediatrics, the scientists utilized RNA sequencing on nasal samples taken during 176 acute respiratory illness episodes.

They identified three unique inflammatory triggers of asthma exacerbations.

The first involved epithelial inflammatory pathways, which were heightened in children receiving mepolizumab, regardless of viral infection.

The second was macrophage-driven inflammation, specifically associated with viral respiratory illnesses, while the third encompassed mucus hypersecretion and cellular stress responses, which were increased in both treatment and placebo groups during flare-ups.

“We discovered that children who still experienced exacerbations while on medication had reduced allergic inflammation but maintained other residual epithelial pathways that were contributing to their inflammatory responses during exacerbations,” Dr. Kumar explained.

This study emphasizes the intricacies of asthma in children and highlights the necessity for more tailored treatment approaches, according to Dr. Kumar.

As asthma continues to disproportionately affect children in urban settings, the findings from this study could lead to precision interventions tailored to the specific type of inflammation driving each child's asthma, ultimately enhancing the quality of life for young patients, Dr. Kumar noted.