Is Bangladesh Facing an Unprecedented Crisis in Democracy?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Bangladesh's democracy is facing unprecedented challenges.

- Violence and persecution are becoming normalized.

- The rise of Islamist extremism threatens democratic integrity.

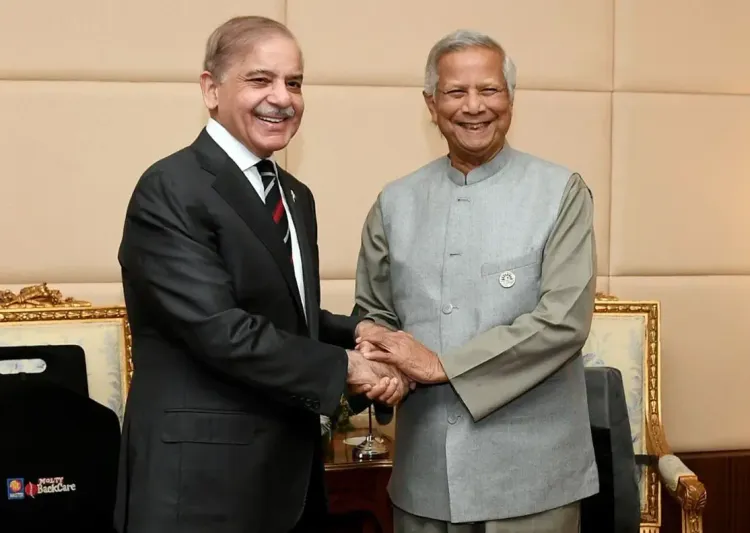

- Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus promises free elections.

- Historical context is vital to understanding current events.

Dhaka: As Bangladesh prepares for its 13th national election scheduled for February 2026, the political atmosphere in Dhaka is fraught with unprecedented challenges. Since August 2024, the country has witnessed a surge in communal violence, mobocracy, ethnic assaults, the rise of Islamist extremism, targeted oppression of dissenting voices, and aggressive historical revisionism, which have become synonymous with the 'new' Bangladesh. Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus, however, has assured that this election will mark Bangladesh's first 'free and fair' democratic transition in 15 years.

The July Uprising, the establishment of an interim government, and the prohibition of the Awami League and its student wing, the Chhatra League, gained legitimacy based on the claim that Sheikh Hasina, the ousted Prime Minister, had jeopardized the nation’s democracy for 15 years.

Concerns have been raised not only by anti-Hasina factions within Bangladesh but also by her political adversaries abroad. Critiques focused on the integrity of the last three national elections, pointing to Hasina's authoritarian tendencies rooted in the concentration of power and her prolonged term, accompanied by numerous human rights violations.

These issues have often been isolated from their historical context. Critics from the West frequently analyze Bangladeshi politics through a Eurocentric lens, trivializing the nation's democratic challenges as mere electoral issues, akin to turnout problems in Denmark. However, the foundation of Bangladesh's democracy is not constructed from ballots but from the blood shed by millions of Bengalis and the struggles against colonial rule, compounded by dual partitions in 1947 and 1971.

Post-liberation in 1971, Bangladesh enjoyed a fleeting democratic period from 1971 to 1975, before descending into military rule until 1990. Thus, Bangladesh's democracy remains relatively young, with anti-democratic forces still active.

A significant threat to the democratic framework has been the resurgence of Islamist politics, which re-established itself under military governance following Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's assassination in 1975. The Jamaat-e-Islami party, a former collaborator with the Pakistan Army, was permitted to re-emerge as a political entity in 1978, contesting national elections under civilian rule. Notably, Jamaat-e-Islami has historically opposed the 1972 Constitution, which enshrines the principles of nationalism, socialism, democracy, and secularism, advocating instead for an Islamic state governed by Sharia law.

Jamaat became the third-largest party in Bangladesh through coalitions with the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), forming governments during the periods of 1991-2006 and 2001-2006, both of which saw an escalation in Islamic radicalism alongside a deepening governance crisis. While Islamist militant groups like Jamaat-ul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) and Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami (HuJI-B) engaged in acts of terror through arson and targeted killings, those in power undermined democratic norms with voter manipulation, rigged elections, and rampant corruption.

Sheikh Hasina's second term began amidst a politically charged environment that necessitated military intervention for the survival of democracy. The 2008 elections that brought her back to power initiated a new era of liberal democracy. Hasina's political acumen facilitated economic and infrastructural growth while fostering democratic continuity through a balanced civil-military relationship. In contrast to neighboring South Asian countries facing severe debt crises, Hasina managed to keep the Bangladeshi economy afloat despite various challenges.

One of the most significant achievements of the Awami League-led government has been Hasina's stringent approach to combatting prolonged Islamist extremism. The renewed wave of extremist violence by groups like Neo-JMB and Ansar-ul-Bangla Team, targeting secular activists, bloggers, artists, and minority groups since 2013, was met with a 'zero-tolerance' policy. Nationwide counter-terrorism operations and stringent laws effectively neutralized terrorist strongholds and received international acclaim.

During her leadership, Hasina also sought justice for victims of the 1971 Liberation War by reviving the International War Crimes Tribunal, ensuring that collaborators of the Pakistan Army faced prosecution. She acknowledged the plight of the war rape survivors, recognizing them as liberation fighters while providing financial assistance to their families. Hasina's administration thus restored the true legacy of 1971, albeit at the dismay of Jamaat-e-Islami.

Hasina's main political adversaries, such as the BNP and Jamaat, have consistently opposed her Awami League party, positioning it as the sole secular party capable of governance. The 15th amendment introduced in 2011 constitutionally reinstated secularism, which had been removed under Ziaur Rahman's regime in 1977, while still acknowledging Islam as the state religion. Her prolonged tenure has offered protection to minority communities, significantly reducing instances of religious persecution due to proactive measures by the Awami League government. Bangladeshi culture has also been actively promoted through interfaith initiatives and the celebration of festivals, reinforcing the nation’s pluralistic identity.

Sheikh Hasina has proven to be both a stabilizing force and a guardian of Bangladesh's pluralism, ensuring economic and geographical predictability. Despite her shortcomings, she remains the only viable alternative in a state often hostile to democracy, liberalism, and pluralism. Her critics abroad are aware of this reality, although they tend to downplay it.

The current democratic crisis in Bangladesh stems from a significant loophole: the absence of a legitimate democratic opposition. Contrary to the outdated notion that undermining a strong incumbent would revive democracy and pave the way for a credible pluralistic alternative, the existing political landscape reveals a historical pattern. In a fragmented society, power vacuums are often filled not by moderates but by the most organized and violent factions, in this case, the Islamists.

In the political realm, Islamists are now vying for electoral power and advocating for constitutional changes to establish a Sharia-based governance system. Socially, their factions have instigated mob violence and disrupted events celebrating the nation's pluralistic identity.

This counter-revolution has arisen from misguided pursuits for democratic optics, leading to destructive missteps and context-blind activism masquerading as a strategy of value-driven paternalism. While Sheikh Hasina is not without flaws, the collapse of state order would invariably be more detrimental than an imperfect one.

Bangladesh's democracy crisis is dire, with violence and persecution becoming normalized, plunging the nation into a state of instability. Regrettably, the country is likely to bear a heavy toll for this situation.