Is There a Cautious Recovery in India–US Ties After Wobbles in 2025?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- India-US relations have experienced ups and downs in 2025.

- Trade tensions and geopolitical disagreements are significant issues.

- There is potential for a more productive 2026.

- India's trade posture is evolving towards increased openness.

- Agricultural access remains a major challenge in trade negotiations.

Washington, Dec 18 (NationPress) The bond between India and the United States in 2025 has experienced an initial surge of diplomatic activity, followed by tensions related to trade and geopolitical issues. However, it is now showing signs of stabilization as both nations look forward to a potentially more fruitful 2026, according to a senior expert on India based in the US.

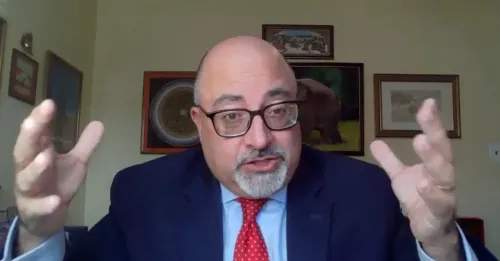

Richard Rossow, who serves as a senior advisor and Chair on India and Emerging Asia Economics at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), shared insights with IANS during an interview, reflecting on the trajectory of bilateral relations over the past year.

Rossow noted that India had an advantageous start in engaging with the Trump administration, pointing to early diplomatic outreach that included a meeting between heads of state and a gathering of Quad foreign ministers.

Nevertheless, he remarked that soon after, differences arose regarding the resolution of the India-Pakistan conflict and concerns from Washington regarding India’s ongoing purchase of Russian oil, which he indicated led to additional trade sanctions.

Despite these challenges, Rossow expressed that the current phase feels more settled. “We don’t have the trade agreement finalized yet, but the sense of daily hostility has diminished,” he stated, suggesting this could pave the way for a more successful year in 2026.

Regarding trade, Rossow acknowledged that India continues to be a difficult partner for US companies, citing regulatory measures implemented since Prime Minister Narendra Modi took office that have made it “more challenging for US companies to export to India.” He noted that some of these restrictions still impact US perceptions, especially during the Trump era.

On a positive note, Rossow pointed out that India's trade dynamics are evolving. He mentioned reductions in tariffs, fewer mandatory local manufacturing requirements, and significant trade agreements with Australia and the UAE. “If you weren’t tracking the nuances, you might have missed how much India’s trade stance has changed,” he argued, asserting that New Delhi increasingly views trade openness as a means to integrate into global supply chains.

Despite political fluctuations, Rossow observed that trade numbers remain robust. “You still see year-on-year growth in both imports and exports,” he noted, adding that policy disputes have not significantly impacted actual trade flows as one might expect.

Looking towards 2025, Rossow predicted that final trade figures would likely reveal “high single-digit growth,” although he flagged a recent decline in Indian exports to the US. He characterized this year’s outlook as “modest growth,” but emphasized that a completed trade deal and the removal of additional tariffs could enhance prospects in the coming years.

Rossow singled out agriculture as a major hurdle to finalizing a deal, noting that the US president is “demanding access to Indian basic agricultural commodities.” He cautioned that this area is “dangerous territory” as many Indian farmers lack alternative employment options, making large-scale liberalization politically and socially sensitive.

Defending New Delhi’s position, Rossow explained that India’s economy is uneven, containing both highly productive services and low-productivity agriculture. “Further liberalization needs to be phased in appropriately to prevent drastic disruptions to people’s lives,” he remarked.

On the investment front, Rossow highlighted recent multi-billion-dollar US commitments to India’s artificial intelligence sector, indicating a long-term strategic vision. “The world will have three major economies,” he stated, predicting that India will evolve into a $20–25 trillion economy by mid-century and will compete with the US and China for global economic leadership.

Regarding reforms, Rossow noted that the Modi government was initially slow in its third term but has recently displayed renewed urgency, citing adjustments to the goods and services tax and legislation to permit 100 percent foreign investment in insurance. He suggested that New Delhi appears to recognize that “the keys to growth lie domestically” and are largely within government control.

Looking forward to 2026, Rossow indicated that the first quarter will be “make or break,” with expectations for a trade agreement, a postponed US presidential visit to India, a Quad leaders’ meeting, and an AI impact summit scheduled for February. He also referenced upcoming state elections as potential factors influencing India’s reform capacity.

Rossow concluded by asserting that India has transformed over the past 11–12 years, establishing a “more robust security posture,” deeper security cooperation with the US, and significant reform efforts, albeit episodically. “The people ties, the commercial ties, security ties, you know, it’s enough glue,” he remarked, suggesting that even amid periods of strain, the relationship has demonstrated resilience.

Over the last decade, India and the United States have consistently expanded their cooperation in defense, technology, and strategic forums like the Quad, even amidst differences in trade policy and global issues. The growth in bilateral trade has positioned the US as one of India’s largest trading partners.