What Can We Learn from the Gen Z Protests in Nepal?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

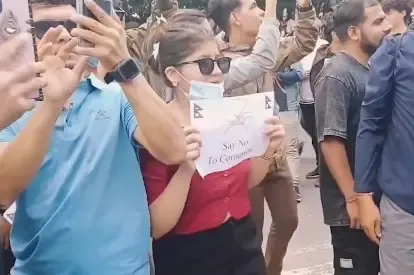

- Gen Z is a driving force behind recent protests in Nepal.

- Demonstrations are fueled by anger towards nepotism and corruption.

- Similar movements in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh highlight a regional trend.

- Grassroots organizing via technology is key to mobilizing youth.

- Maintaining independence from political parties is vital for authenticity.

New Delhi, Sep 8 (NationPress) Violence erupted in Nepal when a significant youth protest escalated into clashes with security forces on Monday, resulting in fatalities. This protest, which emerged as a reaction against nepotism, corruption, and the government's prohibition of various media applications, spilled onto the streets and resulted in physical confrontations.

The small Himalayan nation has a history of upheaval, with young people often leading the charge. Last year, demonstrators advocated for a return to monarchy, over a decade and a half after the royal family was ousted in a violent uprising.

This call for a return to previous governance structures emerged amid persistent political instability, characterized by 13 governmental changes within 16 years.

Currently, these events unfold in the context of youth movements against corruption and nepotism that have led to regime changes in neighboring South Asian nations like Sri Lanka and Bangladesh.

Similar to Nepal, where Gen Z is spearheading the movement, the youth also played a crucial role in the mass protests in Sri Lanka (2022) and Bangladesh (2024).

Gen Z is defined as the cohort born between 1997 and 2012, recognized as the first generation to have predominantly grown up with modern technology, including the Internet and social media.

In both Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, this generation was pivotal in the struggles against their respective governments. Initially, the protests in all three countries were apolitical.

In the early phases, these uprisings aimed to fend off established political parties from taking control of the movement.

In Colombo, rising fuel and food shortages ignited demonstrations led by Gen Z and millennials. What began as sit-ins escalated into extensive occupations of presidential sites, ultimately resulting in the resignation of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Protesters later stormed the presidential residence and the Prime Minister’s office, drawing international attention to their cause. During this time, informal councils were formed to negotiate with authorities.

Numerous reports indicated that political entities were present among the protesters, each with their own interests.

Since the new government took over in 2024, significant shifts in policy and governance have occurred.

In Bangladesh, students ignited mass protests against the government’s job-quota system, claiming it favored political loyalists over merit-based candidates.

As demonstrations intensified, security forces reacted with force. Protesters eventually surrounded the Prime Minister’s residence, prompting Sheikh Hasina to flee the nation on August 5, 2024, effectively concluding her 16-year rule.

Following this, student leaders created the National Citizen Party to participate in future elections and joined an interim government led by Nobel laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus.

An appointed National Consensus Commission began drafting reforms for the constitution and civil service, aiming to enhance transparency and dismantle entrenched patronage systems.

Like in Nepal, the agitation in Bangladesh was driven by tech-savvy young activists who circumvented traditional party structures to organize protests through viral videos and encrypted communications.

Similar to Sri Lanka, Bangladesh’s students succeeded in toppling the government through sustained encampments and mass mobilization.

While Sri Lanka currently has an elected government, Bangladesh has transitioned power to an interim authority, with elections not anticipated in the near future.

Student leaders in Bangladesh quickly institutionalized their movement into a formal political entity; in Kathmandu, Gen Z activists maintain a focus on leaderless coalitions and incremental policy objectives to uphold grassroots integrity.

Nepal’s Gen Z has explicitly chosen not to align with existing political parties. As demonstrated in the other two movements, this stance provides both strength and potential vulnerabilities.

Thus, considering the subsequent transformations in Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte/Colombo and Dhaka, there exists a heightened risk of being absorbed into political party structures.