What Links the Loss of Smell to Alzheimer's Disease?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Microglia disrupt connections between brain regions linked to smell.

- Olfactory dysfunction may precede cognitive decline in Alzheimer's.

- Research involves observations in both mice and humans.

- Phosphatidylserine serves as a signal for microglia to remove faulty neuronal connections.

- Findings could lead to early diagnosis and treatment.

New Delhi, Aug 16 (NationPress) The brain's immune cells might shed light on why a diminishing sense of smell serves as an early indicator of Alzheimer's disease, even prior to the onset of cognitive decline, as suggested by a recent study.

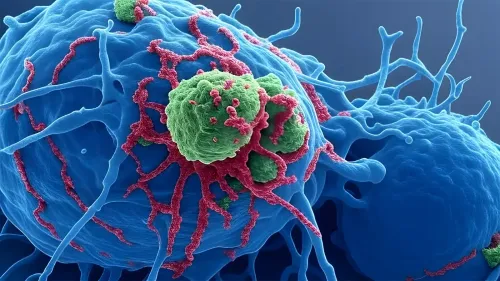

Researchers from DZNE and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU) in Germany discovered that the brain's immune response appears to aggressively target neuronal fibers that are essential for the perception of odors.

This olfactory impairment occurs because the brain's immune cells, known as microglia, disrupt connections between the olfactory bulb and the locus coeruleus. This finding was detailed in a paper published in the journal Nature Communications.

The research, based on insights from both mice and humans, including examinations of brain tissue and PET scans, could assist in creating methods for early diagnosis and, as a result, prompt treatment.

Dr. Lars Paeger, a scientist at DZNE and LMU, explained, "The locus coeruleus governs multiple physiological functions, such as cerebral blood flow, sleep-wake cycles, and sensory processing, particularly the sense of smell."

"Our research indicates that in the initial stages of Alzheimer's disease, alterations occur in the nerve fibers linking the locus coeruleus to the olfactory bulb. These changes signal to microglia that these fibers are either damaged or no longer needed, prompting them to eliminate those connections," Paeger elaborated.

Specifically, the team uncovered signs of changes in the membrane composition of the affected nerve fibers: Phosphatidylserine, a fatty acid typically located within a neuron's membrane, had migrated to the exterior.

"The presence of phosphatidylserine on the outer side of the cell membrane is recognized as an 'eat-me' signal for microglia. In the olfactory bulb, this is usually linked to a process called synaptic pruning, which is designed to eliminate unnecessary or nonfunctional neuronal connections," Paeger explained.

These findings could facilitate the early detection of individuals at risk of developing Alzheimer's, allowing them to undergo thorough testing to confirm their diagnosis before they experience cognitive issues.