What Are the Consequences of Pakistan's Military Dictatorship on Democracy?

Synopsis

Key Takeaways

- Pakistan's military has historically undermined democratic governance.

- Institutional dominance has created a hybrid regime.

- Jinnah's vision for democracy remains largely unfulfilled.

- Military's economic influence complicates governance.

- A credible political movement is essential for true democracy.

Pakistan's enduring battle for democratic governance resembles less a tale of political advancement and more a cautionary tale of institutional overreach.

Although the founding leaders envisioned Pakistan as a republican state back in 1947, the country has persistently struggled to establish a genuine democratic framework. The principal force behind this persistent failure is well-known yet rarely contested: the Pakistan military. Over several decades, it has entrenched itself in the apparatus of political authority, consistently undermining civilian leadership and eroding democratic institutions from within.

Today, Pakistan operates as a hybrid regime—a superficial civilian government masking a deeply entrenched military establishment. In times of heightened public discontent with this arrangement, the military has repeatedly shown its ability to repackage itself as the indispensable guardian of national security. It frequently employs familiar narratives—such as Indian hostility, internal dissent, or foreign conspiracies—often magnified by compliant media and associated non-state actors, to justify its prevailing role. This was particularly apparent when Army Chief General Asim Munir began using politically charged language ahead of the April 22 Pahalgam attack targeting tourists in Jammu and Kashmir, anticipating a strong Indian response that the military elite could leverage to garner public support.

This militarized governance approach starkly contrasts with the political ideals of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan's founding father, who envisioned an Islamic republic rooted in democratic values, institutional integrity, and social-political equality. Notably, in his speech to the 5th and 6th Ack Ack Regiments of the Pakistan Army—units previously part of the British Indian Army—on February 21, 1948, Jinnah urged the military to uphold the principles of 'Islamic democracy, Islamic social justice, and the equality of man' within the newly established nation's borders.

Yet, the institution Jinnah sought to guide soon veered off course. Although his landmark address to the Constituent Assembly is celebrated as a definitive articulation of his vision for Pakistan, it was largely ignored by the Pakistan Army, whose progressive incursions into the political arena steadily eroded the constitutional values advocated by Jinnah. This shift towards militarized governance alarmingly began within the first decade, thus derailing the democratic aspirations that initially fueled the post-colonial nation-building project.

This gradual consolidation of praetorian tendencies—evident in the slow decay of constitutionalism and civilian authority—ultimately led to the full-blown military coup of 1958. In this initial constitutional collapse, President Iskandar Mirza colluded with General Ayub Khan to annul the 1956 Constitution, thereby dismantling the nascent democratic framework. Ironically, Mirza was soon ousted by the very military apparatus he had empowered, ushering in an extended period of authoritarian military governance. This foundational rupture not only solidified the military's hegemonic role within Pakistan's political landscape but also initiated a pattern of systemic instability that ultimately led to the fragmentation of the state with the secession of East Pakistan and the formation of Bangladesh in 1971.

Since then, the military's grip has only tightened. Over the years, it has progressively expanded its reach—not only within the political sphere but also deep into the nation's economic structures. The regime of General Zia-ul-Haq during the 1980s serves as a poignant example. His tenure was marked not only by the entrenchment of military authority but also by a vigorous Islamization campaign that redefined Pakistan's social landscape and further entrenched the military's role as an ideological arbiter.

By 2020, the Pakistan military's economic empire had evolved into a vast, multi-sector corporate entity, valued at over $20 billion. Renowned for its pervasive presence across the economic landscape, the military's commercial and industrial reach spans the production of everyday goods—from sewing needles to bottled water—as well as significant infrastructural projects, including roadworks and property development. A 2016 report to the Pakistani Senate revealed that the armed forces oversee more than 50 business ventures, including Askari Cement, Askari Bank, Fauji Meat, Askari Sugar Mills, shopping centers, and residential housing projects. These enterprises are mainly managed through four institutional bodies: the Fauji Foundation, Bahria Foundation, Shaheen Foundation, and the Army Welfare Trust (AWT).

The consolidation and maintenance of this extensive politico-economic structure have become a central institutional priority for the military establishment. Consequently, the continuation of its hegemonic control over civilian governance is no longer justified solely through traditional security arguments but is now inherently tied to safeguarding its vast material interests and ideological influence—often at the expense of democratic consolidation and civilian empowerment.

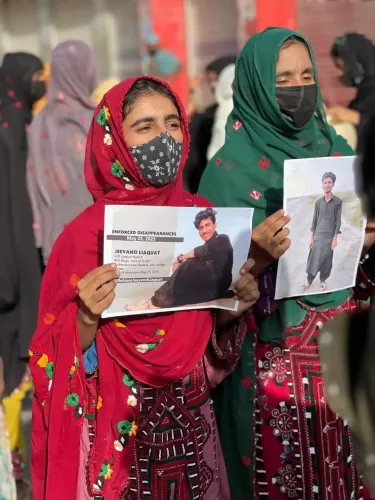

The cumulative effect of this militarized political framework has been the consistent undermining of civilian authority, which has continually struggled to achieve independent legitimacy or institutional continuity within Pakistan's governance system. Consequently, any civilian political figure whose ascent threatens the entrenched dominance of the military establishment has routinely faced sidelining through coercive or extrajudicial means. A notable instance of this trend was the judicial execution of Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1979—a politically motivated act following his dismissal in the 1977 military coup—spurred by his growing popular support and increasing resistance to military oversight.

This historical precedent resonates in the state's ongoing punitive campaign against former Prime Minister Imran Khan, whose current imprisonment is widely interpreted as retribution for his overt challenge to the military's established influence within the political arena. These recurring patterns of suppression highlight the military's enduring aversion to political autonomy and its structural compulsion to maintain hegemonic supremacy over democratic institutions.

These structural imperatives collectively sustain the Pakistan Army's ongoing resistance to any meaningful process of democratic consolidation, thereby entrenching its authoritarian control over state machinery. As such, the system is engineered not for democracy but for containment. The ongoing civil-military imbalance is not incidental; rather, it is systematically reinforced through a complex interplay of institutional self-preservation, economic interests, and ideological dominance. Civilian institutions are allowed to function only to the extent that they do not challenge the military's primacy. This is not governance; it is institutionalized authoritarianism draped in a democratic facade. Breaking free from this cycle necessitates more than fleeting outrage or symbolic acts of dissent. Dismantling military involvement in politics requires a far more ambitious strategy: a sustained, organized, and credible political movement—one capable of confronting both the ideological and material foundations of military rule. Without such a movement, Pakistan will remain ensnared in a state of managed democracy, with its citizens relegated to a system that neither represents nor empowers them.